The Great War – World War I was an extremely bloody war that engulfed Europe from 1914 to 1918 with huge losses of life. Fought mainly by soldiers in the trenches, World War I saw an estimated 10 million military deaths and another 20 million wounded.

The 4th of August 2014 will mark the centenary of the beginning of The Great War.

We would like to mark the occasion by recording details of anyone with a Killamarsh connection who took part in ‘The War to end all Wars’.

Did a member of your family go to war. Do you have any photographs, information or stories that have been passed down through the family.

If you have anything you would like to include in this memorial, please let us know by emailing secretary@killamarsh.org

If you know of anyone who does not have access to a computer who may wish to include any information or photographs, please ask them to contact us by telephoning 0114 2484812.

We look forward to hearing from you.

_____________________________________________________________

KILLAMARSH HAS TWO WAR MEMORIALS, THE ORIGINAL BEING THE STAINED GLASS WINDOW AT ST GILES CHURCH, THE COST OF WHICH WAS RAISED BY THE PEOPLE OF KILLAMARSH FOLLOWING WORLD WAR I.

THERE IS A SECOND WAR MEMORIAL AT THE JUNCTION BRIDGE STREET AND HIGH STREET, THE COST OF WHICH WAS FUNDED BY THE PEOPLE OF KILLAMARSH AND WHICH WAS UNVEILED IN 2011.

THE NAMES OF THE FOLLOWING PEOPLE WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN WORLD WAR I APPEAR ON BOTH MEMORIALS.

WE WILL REMEMBER THEM

Sacred to the memory of the brave of this Parish who fell in the Great War 1914 – 1918

F. Adams

H. W. Bamborough

H. Batty

F. Drakett

J. W. Drakett

W. Drakett

H. Draper

C. C. Elliott

G. H. Fields

T. A. Godber

B. Hall

H. Handbury

A. Hanson

J. F. Hobson

J. W. Howe

W. Jackson

R. Leverton

J.E. Lewis

J. Mangham

G. A. Northridge

G. Price

J. W. Scott

W. Shepherd

R. Smith

W. Smith

G. A. Stenton

G. H. Stones

J. Stones

A. F. Swindell

J. W. Tantram

F. Taylor

G. H. Taylor

J. F. Taylor

W. Thompson

S. Tongue

J. Walker

S. Whitfield

W. Whitham

P. Willis

C. Wilson

E. Worthington

“May they rest in peace”

______________________________________________________________________

BELOW IS INFORMATION AND PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT THE MEN WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN WORLD WAR I AND WHOSE NAMES APPEAR ON THE WAR MEMORIAL IN THE VILLAGE AND ALSO OTHERS WITH A KILLAMARSH CONNECTION

If you would like to add anything to this section please email your information to secretary@killamarsh.org

ARTHUR HANSON

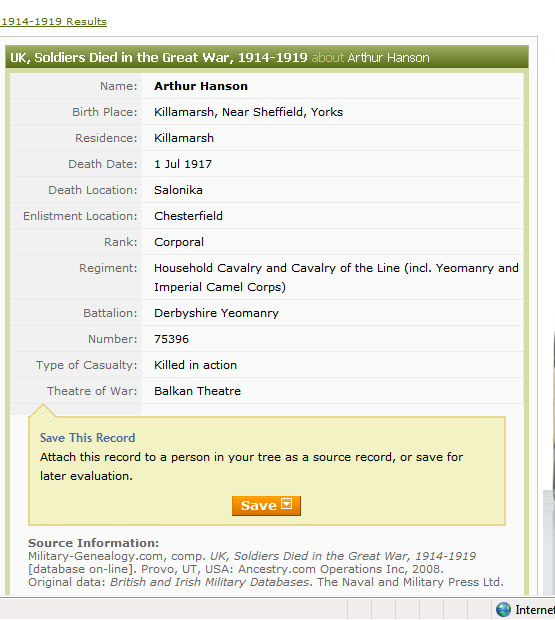

Name: Arthur Hanson

Birth Place: Killamarsh, Near Sheffield, Yorks

Residence: Killamarsh

Death Date: 1st July 1917

Death Location: Salonika

Enlistment Location: Chesterfield

Rank: Corporal

Regiment: Household Cavalry and Cavalry of the Line (incl. Yeomanry and Imperial Camel Corps)

Battalion: Derbyshire Yeomanry

Number: 75396

Type of Casualty: Killed in action

Theatre of War: Balkan Theatre

Cemetery: Struma Military Cemetery, Greece

Above: Struma Military Cemetery

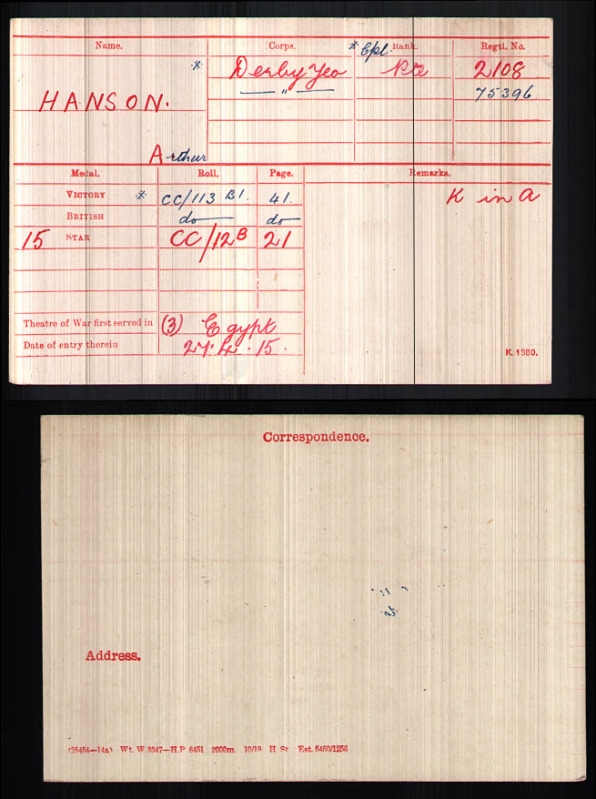

Arthur Hanson was a Corporal in the Derbyshire Yeomanry whose name appears on the War Memorial in Killamarsh.

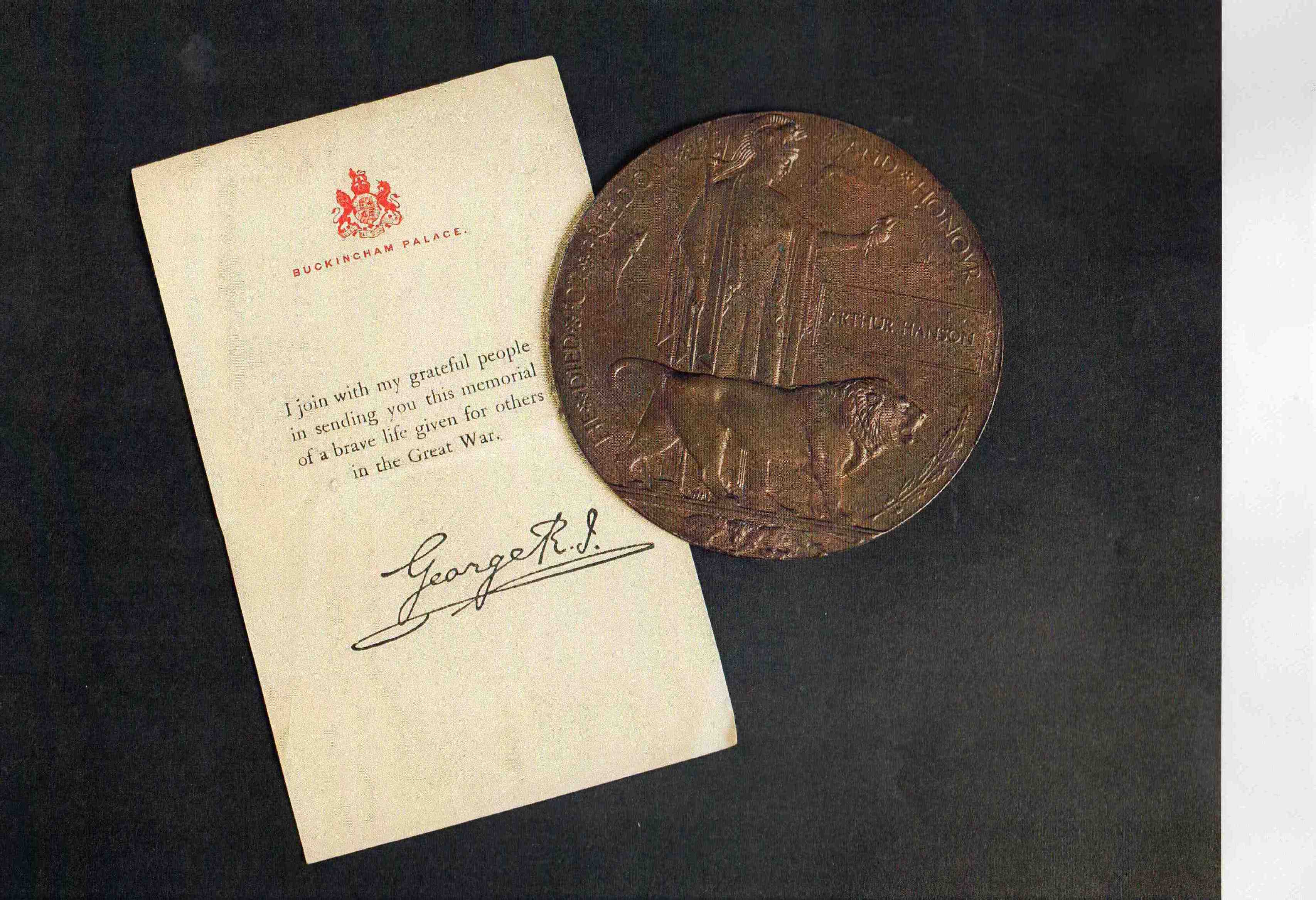

Above: Arthur’s Death Plaque

Arthur was killed on the 1st of July 1917 in Salonika, Balkans Theatre of War and is buried in Struma Military Cemetery. According to records, not verified, on the day of his death there was no battle in the area in which he was stationed. It is, therefore, surmised that he could have been killed whilst on a patrol.

Below: Arthur’s Service Medal

Above: Arthur’s Medals List

Arthur had a number of brothers and sisters:

Mary Ellen Chapman

Alice Smith

William Smith

Elizabeth Smith

John Gardner Hanson

Above: Arthur Hanson’s War Record

Fanny Chapman, my Great Grandmother was born in Killamarsh in 1871 and was married to William Henry Northall who was born in 1870 in Staveley and Christened in Killamarsh on 29th March 1871. My Great Grandfather was a miner and an Officer in the Salvation Army and as such moved around the North of England.

Fanny and William Northall (my Great Grandparents) had three children, one of whom was Florence Northall, my Grandmother.

In 1913, Florence gave birth to a baby girl, illegitimately, in the Salvation Army Hostel in London. Arthur Hanson was the baby’s father.

Florence and Arthur never married, and in 1916 Florence married Hubert Henry Gough, my Grandfather.

Arthur’s last Will and Testament states that his residence in 1914 was the Midland Hotel in Killamarsh (which it is thought may have been owned by Arthur’s parents).

Above: Arthur’s Headstone

According to his Will Arthur was a wealthy man with a number of properties in Eckington and Sheffield. He also had shares in the Killamarsh Gas Company and Tenants Brewery.

Thank you to Eric Gough of Birmingham (originally from Leamington Spa) who sent us the information and photographs.

_____________________________________________________________________

THE SHERWOOD FORESTERS

The 1st Battalion, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment

The 1st Battalion, The Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment) were in Bombay, India when war broke out in August 1914.

They returned to England, landing at Plymouth on the 2nd of October, 1914 and joined 24th Brigade, 8th Division at Hursley Park, Winchester. They proceeded to France, landing at Le Havre on the 5th of November a much needed reinforcement to the BEF and remained on the Western Front throughout the war.

In 1915 they were in action at The Battle of Neuve Chapelle, The Battle of Aubers and The action of Bois Grenier. On the 18th of October, 1915 24th Brigade transferred to 23rd Division to instruct the inexperienced troops.

In March 1916 23rd Division took over the front line between Boyau de l’Ersatz and the Souchez River in the Carency sector from the French 17th Division, an area exposed to heavy shelling. In mid April they withdrew to Bruay returning to the Carency sector in mid May just before the German attack on Vimy Ridge, in the sector to their right. On the 15th of June, 1916 24th Brigade returned to 8th Division. In 1916 they were in action at the Battle of The Somme.

In 1917 they fought in the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line and then moved to Flanders and were in action in The Battle of Pilkem and The Battle of Langemarck.

In 1918 they saw action during The Battle of St Quentin, The actions at the Somme crossings, The Battle of Rosieres, The actions of Villers-Bretonneux, The Battle of the Aisne, The Battle of the Scarpe and The Final Advance in Artois including the capture of Douai.

___________________________________________________________________

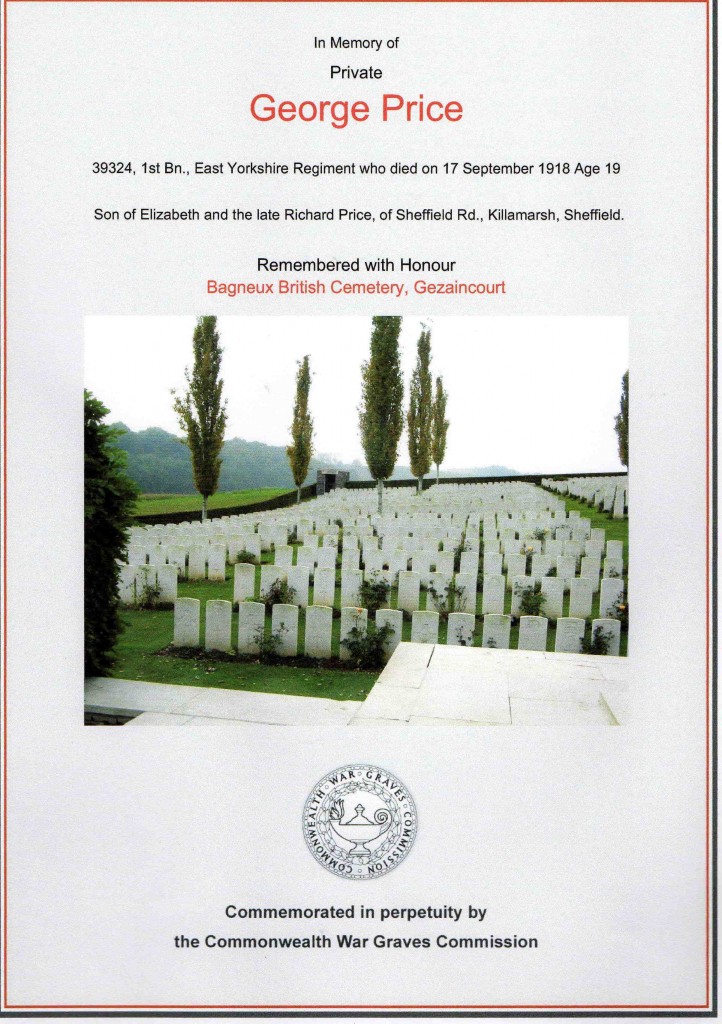

In Memory of Private George Price, 39324, 1st Bn., Yorkshire Regiment

Died on 17 September 1918 Age 19

___________________________________________________________________

FRED GREAVES VC

(16 May 1890 – 11 June 1973)

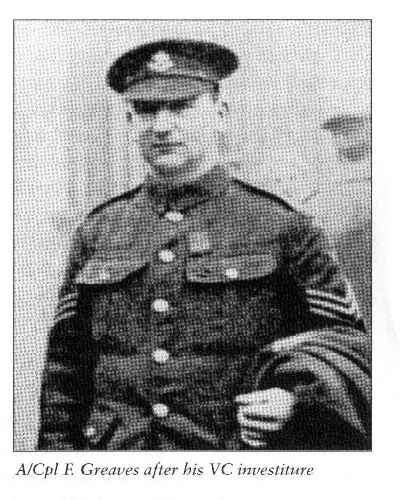

Fred Greaves was born on 16 May 1890 in Killamarsh. He was 27 years old, and an acting Corporal in the 9th Battalion, The Sherwood Foresters (The Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment) in the World War I when he performed a deed for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

The Victoria Cross is the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

On 4 October 1917 at Poelcapelle, east of Ypres in Belgium, the platoon was held up by machine-gun fire from a concrete stronghold and the platoon commander and sergeant were casualties. Corporal Greaves, followed by another NCO, rushed forward, reached the rear of the building and bombed the occupants, killing or capturing the garrison and the machine-gun. Later, at a most critical period of the battle, during a heavy counter-attack, all the officers of the company became casualties and Corporal Greaves collected his men, threw out extra posts on the threatened flank and opened up rifle and machine-gun fire to enfilade the advance.

He later achieved the rank of Sergeant. Fred died in Brimington, near Chesterfield on 11 June 1973.

His Victoria Cross is displayed at the Sherwood Foresters Museum, Nottingham Castle.

The Battle of Poelcappelle

The Battle of Poelcappelle on 9 October 1917 marked the end of the string of highly successful British attacks in late September and early October 1917, during the Third Battle of Ypres.

Only the supporting attack in the north achieved a substantial advance. On the main front the German defences withstood the limited amount of artillery fire achieved by the British after the attack of 4 October. The ground along the main ridges had been severely damaged by artillery fire and rapidly deteriorated in the rains, which began again on 3 October, in some areas the ground became a swamp. Dreadful ground conditions had more effect on the British, who needed to move large amounts of artillery and ammunition to support the next attack.

The battle was a defensive success for the German army, although costly to both sides. The weather and ground conditions put severe strain on all the infantry involved and led to many wounded being stranded on the battlefield. Early misleading information and delays in communication led Plumer and Haig to plan the next attack (the First Battle of Passcendaele on 12 October) under the impression that a substantial advance had taken place at Passchendaele ridge.

Above: Poelcapelle, Belgium 1918 – Corporal Greaves won his VC in brutal, hellish conditions

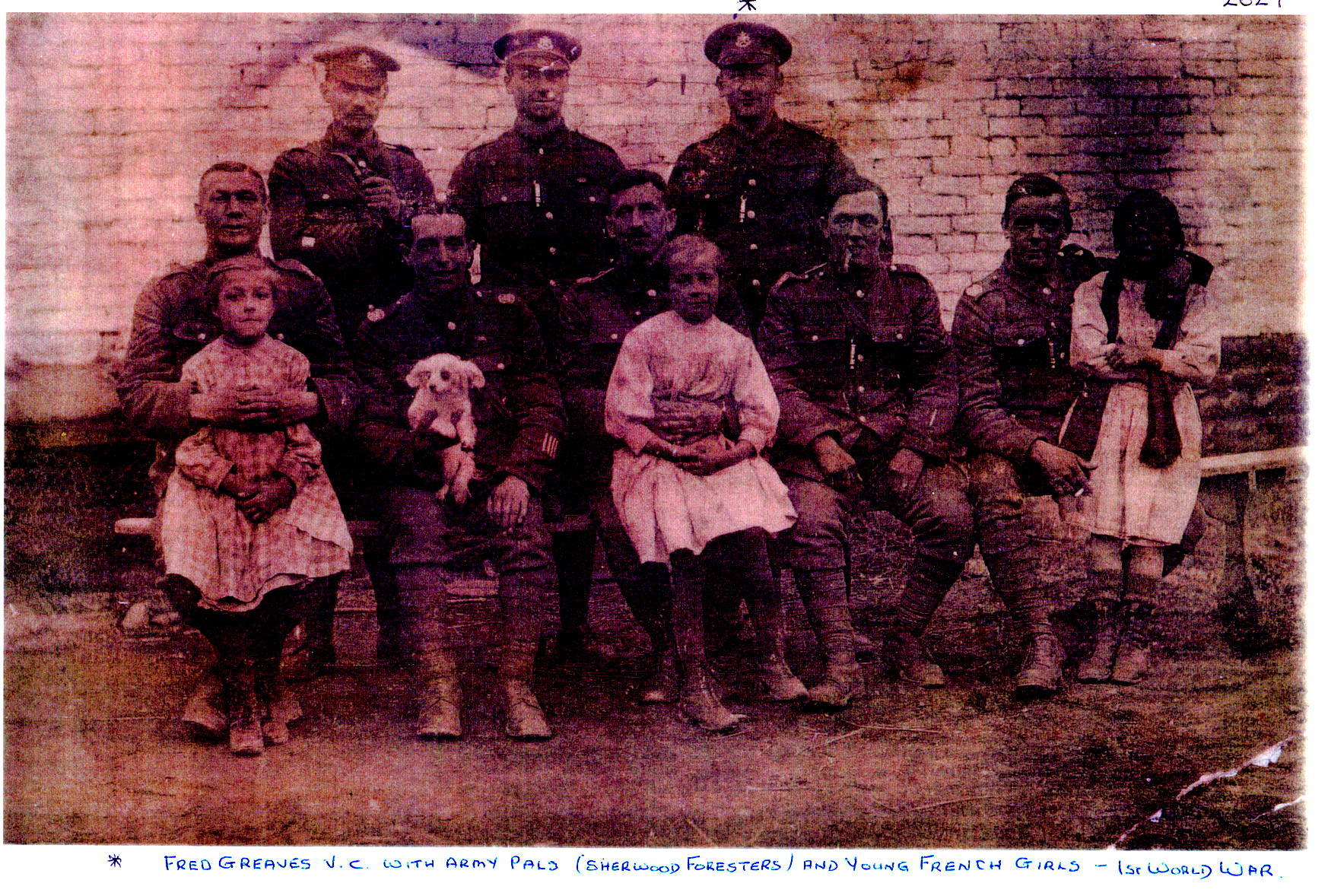

Above: Fred Greaves with Pals and kids. So close to the death and carnage of the war – soldiers, children and a dog.

The following is by kind permission of Steve Morse

Fred Greaves served in the 9th (Service) Battalion, Sherwood Foresters. He and they saw service in Gallipoli, The Somme, Loos, Flanders and the last 100 days – The road to victory.

His daughter Hazel and I have talked many times about her Dad. He seems to me to be the type of man you would want next to you whether in war or peace. An ordinary man who on 4th October 1917 at Poelcapelle did an extraordinary thing.

There are number of stories but perhaps the one I find most interesting is:-

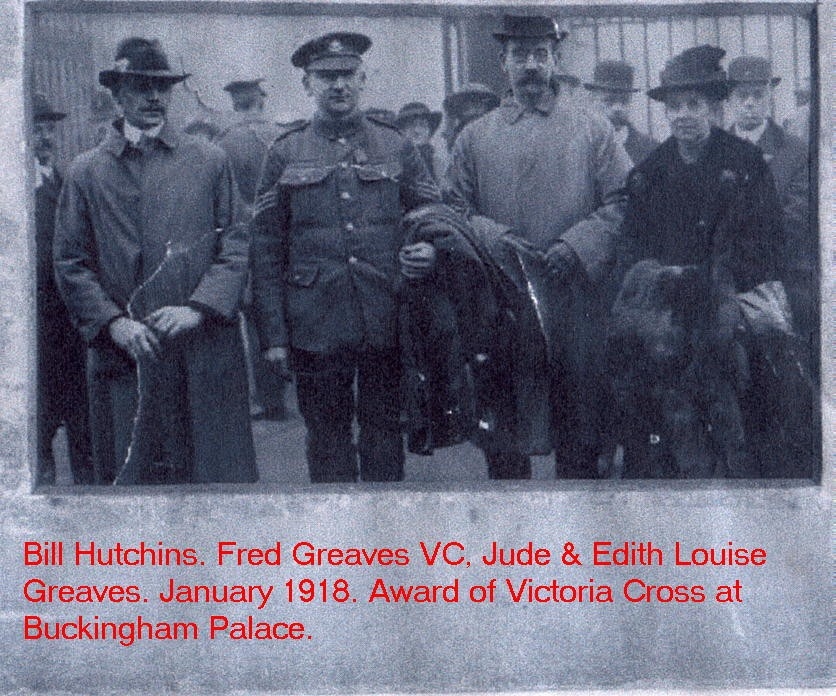

Fred arrived back for leave prior to his VC investiture and his uniform was somewhat the worse for wear. He was told that a new one would be provided for his date at the Palace.

On his return from Derbyshire by train, he was therefore in Civvies. A ‘lady’ also on the train approached Fred and gave him a white feather. Fred said nothing to her.

Above: Corporal Greaves with his parents after he was awarded the Victoria Cross at Buckingham Palace.

Above: Fred Greaves’ medals.

THE CAFÉ AT POELCAPELLE

The people of Poelcapelle in Belgium, where Fred Greaves won his Victoria Cross, still regard him as a hero.

One young couple, the owners of the Café Zwaan, are at the forefront of keeping his memory alive.

A memorial plaque to Fred on the Café wall proudly tells visitors how much they owe to him and his colleagues.

The Café at Poelcappelle

Photograph courtesy of Sally Mullins and the Brimington Memorial website

_________________________________________________________________

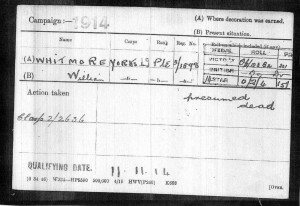

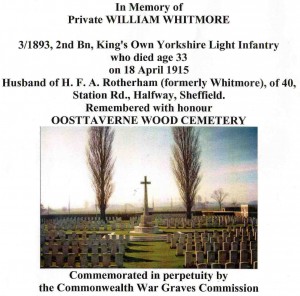

RON MARSHALL has given us the following information about his Grandfather Private William Whitmore who was killed in action age 33 on 18 April 1915.

Private William Whitmore, 3/1893, 2nd Bn, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry was killed on 18 April 1915, aged 33, during an attack on Hill 60.

On 18th April, the 2nd Battalion moved up from Ypres to Larch Wood and took part in an attack on Hill 60.

The following is a quote from ‘British Battalions in France and Belgium, January to June, 1915, by Ray Westlake.

‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies led assult at 6.00 pm. War Diary records the men being met by a hail of artillery, machine-gun and rifle fire immediately they left their trenches. These companies however reached the base of the hill and dashing up the slope crossed the German parapet and the crest of the hill was retaken. Position held after heavy bombardment and counter-attacks. Furious combats took place in the craters – which were filled with killed and wounded. Rifles became jammed with the heat of firing – grenades and ammunition could not be brought forward. War Diary notes that if it were not for the rifles and ammunition left by the fleeting Germans, which the men used, the hill would have been difficult to hold. Relieved at dawn 19th. Casualties – 239 killed, wounded or missing.

OOSTTAVERNE WOOD CEMETERY – BELGIUM

Oosttaverne Wood Cemetery is located 6 km south of Leper town centre on the Rijselseweg N336 connecting Leper to Lille. From Leper town centre the Rijselsestraat runs from the market square, through the Lille Gate (Rijselpoort) and directly over the crossroads with the Ieper ring road. The road name then changes to the Rijselseweg. 3 km along the Rijselseweg the road forks with the N365. The N336 is the left hand fork towards Lille. The cemetery is located 2 km after this left hand fork on the right hand side of the road.

Above: William Whitmore’s grave in Oosttavern Wood Cemetery in Belgium (Photo courtesy of Keith Hodkin)

The “Oosttaverne Line” was a German work running northward from the River Lys to the Comines Canal, passing just east of Oosttaverne. It was captured on 7 June 1917, the first day of the Battle of Messines, the village and the wood being taken by the 19th (Western) and 11th Divisions. Two cemeteries, No 1 and No 2, were then made by the IX Corps Burial Officer on the present site and used until September 1917. They are contained in Plots I, II and II of the present cemetery, which was completed after the Armistice when graves were brought in from the surrounding battlefields (including many from Hill 60) and from German cemeteries in the area.

During the Second World War, the British Expeditionary Force was involved in the later stages of the defence of Belgium following the German invasion in May 1940, and suffered many casualties in covering the withdrawal to Dunkirk.

The cemetery contains 1,119 First World War burials, 783 of which are unidentified. Scattered among these graves are 117 from the Second World War, five of them unidentified. The cemetery was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens.

THE FOLLOWING IS AN EXTRACT FROM TOM MORGAN’S YPRES BATTLEFIELD GUIDE and gives an insight to the horrors of Hill 60.

With the kind permission of Tom Morgan

HILL 60 – “HELL WITH THE LID OFF”

When I was a small boy I lived with my great-uncle and great-aunt. They were the brother and sister of my grandparents. Uncle Tom was my grandmother’s brother, and Aunt Lizzie was my grandfather’s sister. I lived with them from about the age of five until I was sixteen.

They were the possessors of the Family Bible – one of those large, illustrated editions which contained special sections at the beginning for recording family birth and death dates. This bible was also a repository of small, mostly thin items of memorabilia such as newspaper cuttings, important letters and so on. However there was one item kept in the bible for safe keeping which was always easy to find because it was slightly thicker than the rest and forced the pages apart a little, making it always fall open at that particular page. It was a small envelope filled with tiny, dried flowers and written on the envelope were the words, “Flowers from Hill 60, 1914-18 War.”

A friend of my uncle had been wounded at Hill 60 in 1915 and, trapped out in the open, he had been obliged to keep as still as he could and wait until nightfall to see if he could make his way back to his own lines. Having spent most of the day afraid to move his head, he decided, when night fell and it was time to begin the crawl back to the British trenches, that he would fill his pocket with the flowers which, for so many slow hours, had been the only things within his field of vision. He later gave some of the flowers to friends and relatives as keepsakes and the little packet kept in the family bible was my uncle’s share.

I can’t recall when I first saw these flowers but it must have been when I was very small and the name must have stuck with me because I can’t remember a time in my life when I didn’t know that Hill 60 was a place where soldiers had died in the World War. The name always fascinated me as a child – it seemed such a technological, modern name somehow.

It’s strange that such a terrible place – for it was certainly one of the most feared places in the whole of the Ypres salient, and one which was never quiet – should be so insignificant when you look at it. “Hill” is certainly something of an exaggeration. From top to bottom, Hill 60 is not much higher than a bedroom window. It was formed in the 1860s, when the railway come to Ypres and a line was built from the city to Comines. To get to Comines, the railway had to climb the Northern end of the Messines Ridge and, as steam engines are not very good at climbing hills, a cutting was dug to ease the gradient. The spoil from the work was dumped in three piles at the top of the climb, making three little hills. The biggest of these was marked on the British maps as “Hill” with its height above sea level in metres also given so it appeared as “Hill 60” and this became its name.

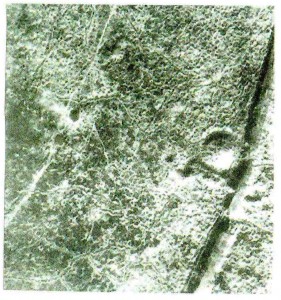

Above: Hill 60 from the air in 1917. The large crater can be clearly seen, beside the railway line.

In their usual methodical way, the Germans, when they dug in in the first winter of the war, placed their trenches on the high ground almost surrounding Ypres like a skewed question-mark including the Messines Ridge. This gave them a distinct advantage in terms of observation and Hill 60 – a small hill on top of a small ridge – was a bonus. Having shelled away most of the trees and buildings between Hill 60 and Ypres, the Germans could take up their prismatic binoculars and enjoy an uninterrupted view of the city itself and the whole of the intervening countryside. The observation bonus is still obvious today. Standing on Hill 60 and looking towards Ypres, it’s easy to appreciate how, in those days, an observer on the hill would be able to see almost any significant movement. I have often read in soldiers’ memoirs how a group of men about a seemingly innocent task, not drawing attention to themselves in any way, would suddenly find themselves as the receiving end of a short and accurate period of artillery fire. Shells, it seemed, would often begin to fall upon a particular spot just as the men themselves reached it. The view from Hill 60 shows how an artillery observer could amuse himself by indulging in a little personal sniping, even shelling unlucky individuals who just happened to be walking towards a point in a track on which he has previously registered his guns.

Harassing individuals or small groups is one thing however. Quite another is the ability to observe and monitor more potent movements of men and material from Ypres towards the trench-lines. A British officer who was able to enjoy the same view after his men had helped capture the hill in 1915 remarked that he thought it a wonder that the Germans had allowed anyone to live at all during the previous few months, so commanding was the view. Because of this, the Allies were prepared to risk a great deal to get the Germans off the crest of Hill 60 and the Germans, for their part, were extremely tenacious in holding onto it.

The first serious fighting took place early in the war, when the French army manned the Allied trenches around Hill 60. There was much small-scale shallow mining and the craters can still be seen, near the road. These craters date from the French occupation in 1915.

In that same year the British took over the sector. Hill 60 already had a fearsome reputation and more than lived up to this under the new occupancy. In 1915, especially around April and May, the hill was the scene of some of the most brutal fighting as possession of the hill passed to and fro. At times, the gentle slopes were littered with corpses and the place was a nightmarish place of smoke, noise and the horror of hand-to-hand fighting. Attack followed counter-attack as the armies struggled to gain or maintain supremacy, and with men caught out in the open during these actions, every square metre of Hill 60 became the scene of somebody’s private battle and, possibly, of someone’s unknown grave.

This period of feverish activity ended with the Germans still in control of the hill, and major attacks ceased for a while but all the same, Hill 60 was never quiet. With the enemies so close, it was always a place of high tension and danger. It was always a place to be feared, and no-one took any unnecessary risks there. There was always enough risk as it was. For example, the 1st Battalion of the Dorsets lost 16 men in a very short time one day in June, 1915 when the Germans opened a whirlwind bombardment for no apparent reason. The bombardment ended as suddenly as it had begun, without being followed by any attack or raid. There was a trench marked on the map as “Trench 39” which ran round the hill roughly following the line of the far side of the road as it is today and the Dorsets were in the section which lay between the present day museum and the railway bridge with the main weight of the bombardment being directed at them. After the shelling had stopped the Dorsets took stock of the damage. Large sections of the trench had been blown in and would have to be repaired that night. 16 men had been killed. One was found in eight pieces. Two couldn’t be found at all, at the time. Their bodies were found later, over a hundred yards away, on the other side of the railway. This was a typical “quiet” day on Hill 60.

Hill 60 was chosen as the position of the most northerly of the mines placed under the Messines Ridge in preparation for what came to be known as the Battle of Messines, which opened on 7th June, 1917. The underground gallery dug to lay the mine, was 1,380 feet long – one of the longest of the Messines Mines, and the Hill 60 tunnellers soberly declared that their target was Germany itself, and their tunnel was officially known as “The Berlin Sap.” Quite apart from the considerable distance to be dug to reach a spot below the strongest German positions on Hill 60, the tunnellers had more work to do, because just before it reached Hill 60, the tunnel branched to provide a second gallery running off to another mine placed beneath the position known as “The Caterpillar” which was the second “hill” formed from the spoil from the railway cutting, on the opposite side of the track. (From the air, it can be seen that the Caterpillar crater is water-filled, unlike the Hill 60 one which is always dry. The many tunnels which still lie under the hill allow rainwater to drain away easily, so the Hill 60 crater remains a dry, saucer-shaped one.)

The tunnellers placed their charges – 45,700 pounds of ammonal plus 7,800 pounds of guncotton making a total of 53,500 pounds, under Hill 60 and 70,000 pounds of ammonal under the Caterpillar – and moved on to the next phase, that of protecting their tunnels from German counter-mining. The Hill 60 mine would have to lie in wait for ten months before it was detonated, and the caterpillar mine, eight months. On the day, both mines exploded correctly and on time. Immediately afterwards British troops stormed the hill and captured it. It remained in British hands until the German advance of 1918.

Hill 60 Today

In contrast to its earlier evil reputation, Hill 60 is known as a quiet spot now, even in these days of growing numbers of battlefield visitors, and if you do visit, you will probably find that you have the place more or less to yourself. This makes it something of a secret place for the duration of your visit, and this makes it easier for you to look and think. After the war, it was left as it was, a memorial to the thousands of soldiers who still lie on it, buried or blown to pieces in the surface fighting, or buried in the many tunnels below it. The shell-holes and craters, their outlines softened by the hand of nature, are still there, along with the smashed remains of concrete German dugouts and one fairly intact British one (built on the top of an earlier, German one) which looks like a sinister, alien face. The view across country to Ypres is still impressive.

The 1917 crater is still there, close to the railway cutting. The strong-point which used to be above the crater, with its machine-gun posts and blockhouses, was vaporised in the explosion, of course, along with a garrison of about 600 Germans, but the smashed remains of other concrete fortifications can be seen here and there in the grass nearby. The smaller craters of the relatively shallow mines dug by the French can also still be seen, among the trees nearer to the road.

There are four significant memorials on Hill 60 – a lot for such a small place. The first one the visitor is likely to notice is the one on the very top of the hill. This is the Memorial to the Queen Victoria’s Rifles – 9th (County of London) Battalion, the London Regiment. This was a Territorial Army battalion and it was on Hill 60 that Lieutenant Geoffrey Harold Wooley became the first Territorial Army soldier to win the Victoria Cross (and the first of five men to win the VC at Hill 60) when, finding himself the only officer on the Hill, and with only a few men, he organised his small force and successfully held on to his trench until relieved, fighting off several attacks while doing so, and being under continuous shellfire the whole time. Lieut. Wooley survived the war and was one of the VC holders chosen to form the Honour Guard at the funeral of the Unknown Warrior. He became a priest after the war and died in 1968.

Above: Photo from cigarette card courtesy of Martin Hornby.

The Memorial was damaged during the second World War and the one to be seen today is the restored version. The Queen Victoria’s Rifles have their memorial in this prime spot on the Hill because after the war, they bought the land in order to ensure its preservation and for many years Hill 60 still had its trenches, shell-holes and dug-outs accessible to visitors. The Hill is now owned by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission which maintains it as a memorial to the hundreds of missing soldiers know to be still buried there.

At the foot of the hill, near the road and quite close together are three more memorials. The smallest one is a long, low stone which gives a very good account of the wartime history of Hill 60. Nearby, within a little enclosure is the Memorial to the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company. Like the QVR Memorial on top of the Hill, this memorial was also damaged in the second World War and has some bullet holes.

A little further along the road, at the far end of a small car-park, is the Memorial to the 14th Light Division. This originally stood in Railway Wood, some distance away from Hill 60 but it became threatened by encroaching vegetation and it was dismantled, restored and re-erected here on Hill 60 in 1978.

(A further memorial, from the second World War this time, can be seen just beside the railway bridge next to the car park. This remembers two Belgian civilians who were shot by the Germans.)

Of course, when we we consider what there is left at Hill 60 to remind us of the war years, we should not forget that several hundreds of soldiers still lie on the Hill, their bodies buried by shelling or lost in the underground tunnels, posts and dugouts. These men are still here, too.

Just across the road is the Cafe/Museum, the modern-day desendant of an earlier one started by a small group of enterprising ex-servicemen who “stayed on” after the war. Outside you will see some rusting (though relatively complete) trench mortars, weapons which could be brought right up into the trenches and which enabled the German defenders of Hill 60 to bring artillery fire instantly to bear on the British trenches at the first sign of trouble.

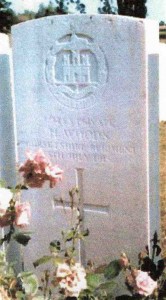

The place where the tunnel for the big 1917 mine began can still be found, too, but you will have to leave Hill 60 to find it. The site – the start of the Berlin sap – is just beyond the wall of Larch Wood (Railway Cutting) Cemetery, a few hundred metres away, where a plantation of larches once grew, and where a fold in the ground gave some cover for dugouts, with the smashed route of the railway being used as a communication trench from there. To reach the cemetery, you will have to leave the Hill 60 site and turn left, crossing the railway bridge. At the t-junction, turn right and look out for the sign (on the right of the road, and next to a little house) pointing the way to the Cemetery. The cemetery is difficult to get to by car as the approach is via a deeply-rutted farm track which crosses the railway at a crossing without barriers, so extreme care is needed, and there is little room to turn a car round for the return trip. But if you do enter the cemetery, walk down the long grass path and keep on walking directly to the far wall. Look over it and the grassy hummock a few metres beyond is the place where the fabled Berlin Sap began. When the tunnel was being dug, the cemetery was already there. In walking to look for the remains of the tunnel entrance, you will have walked past the 16 Dorsets killed in the no-reason bombardment that day in June, 1915. They are buried side-by-side in Plot 2, Row J and among these graves is that of 3/7283 Private Harry Woods, of Shaftesbury, Dorset, who was the man who was found in eight pieces.

I have mentioned Pte. Woods twice in this article and he is mentioned elsewhere on this site. This is not because of any fascination with the exceptionally gory details of his death, but because of the inspiring circumstances of his burial, when his friends, shocked and shaken in the midst of the smoking ruins of their trench after the whirlwind bombardment, still saw it as time well spent to collect his remains and carry them back to this little cememtery and bury him in his own grave, along with the others. For me, the grave of Pte. Woods typifies both the Horror of Hill 60 and the Spirit of Remembrance. I have a photograph of his grave on my desk, always.

Copyright Tom Morgan, January 2003

________________________________________________________________

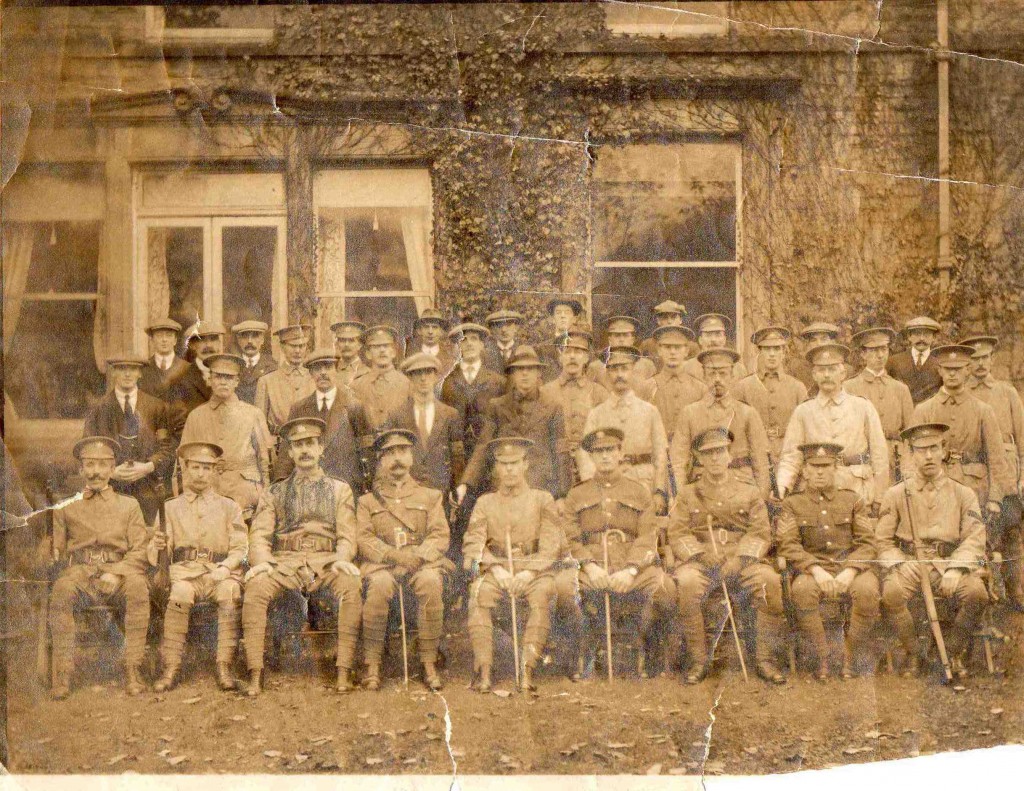

Pictured above: Killamarsh Home Guard 1914-1915

________________________________________________________________

PRIVATE BERTRAM HALL

Private Hall did not return from the War. His name appears on the Killamarsh War Memorial.

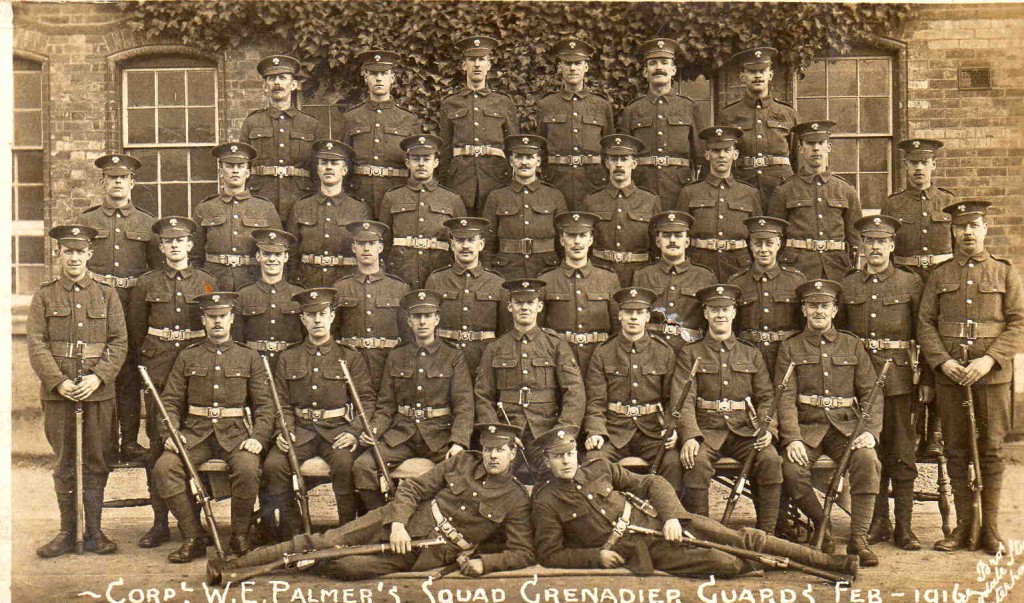

Private Bertram Hall, 24935 4th Battalion Grenadier Guards

Mail from home for Private Bertam Hall

Corporal W.E. Palmers Squad – February 1916. Private Bertram Hall reclining bottom left.

________________________________________________________________

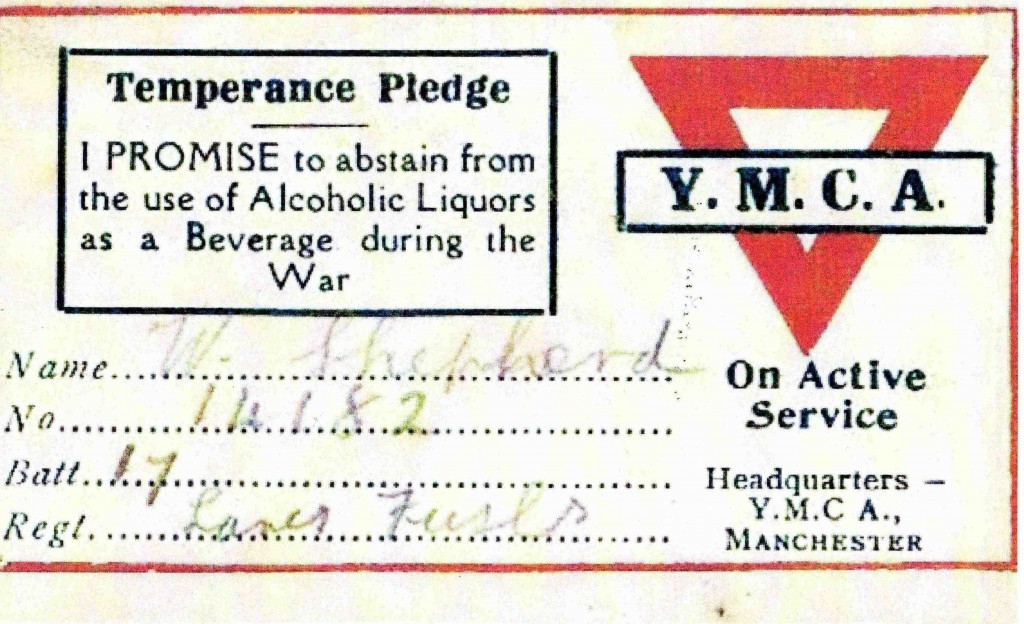

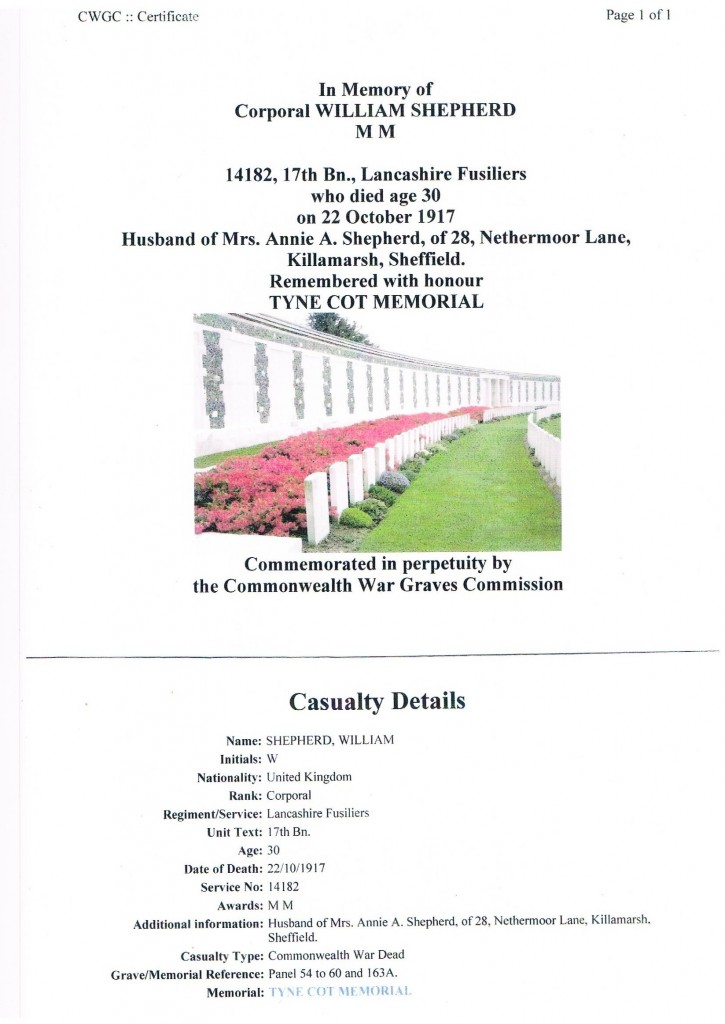

WILLIAM SHEPHERD (1887 to 1917)

The following information has been given to us by June and Melvin Shepherd (Melvin is Corporal William Shepherd’s grandson).

William Shepherd with his family. Corporal William Shepherd was killed in action on 22nd October 1917 age 30. This was the last photograph taken of William – pictured with children William (on his knee), Albert, Emma (born 1912) and Eliza Ann (born 1914) and William’s wife Annie Amelia.

ABOVE: William Shepherd’s Temperance Pledge during World War I.

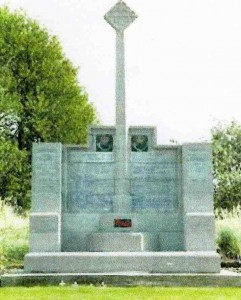

ABOVE: War Memorial for Corporal William Shepherd.

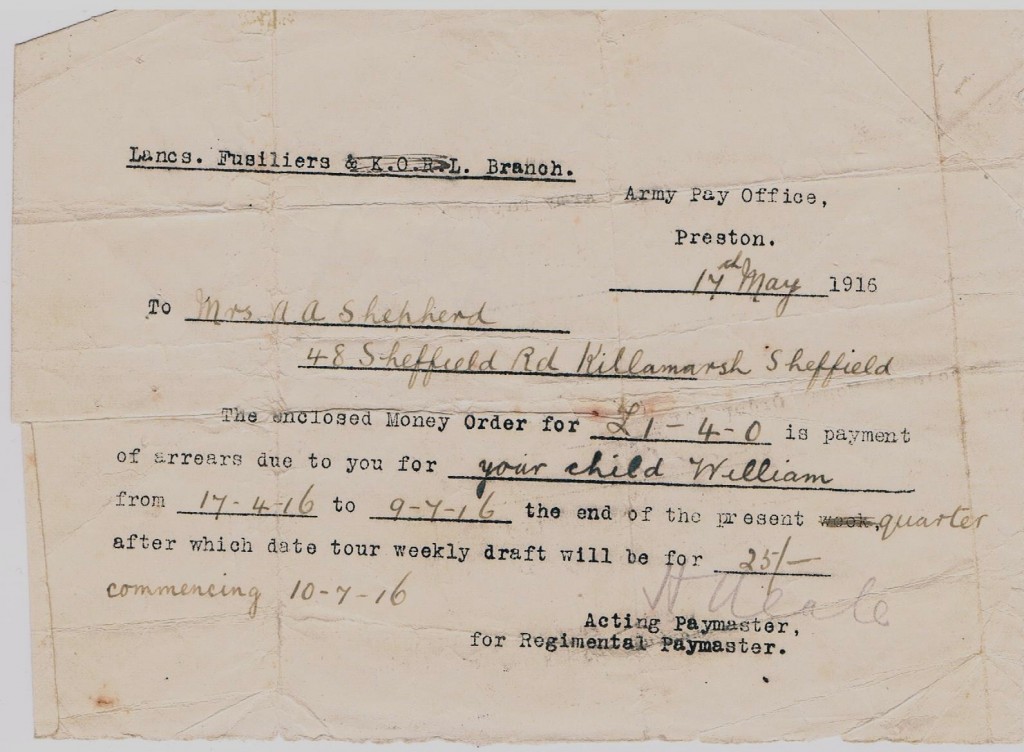

ABOVE: Money Order sent to Annie Amelia Shepherd for her 4th child, William Shepherd (Corporal William Shepherd’s son).

ABOVE: Corporal William Shepherd’s World War I Medals.

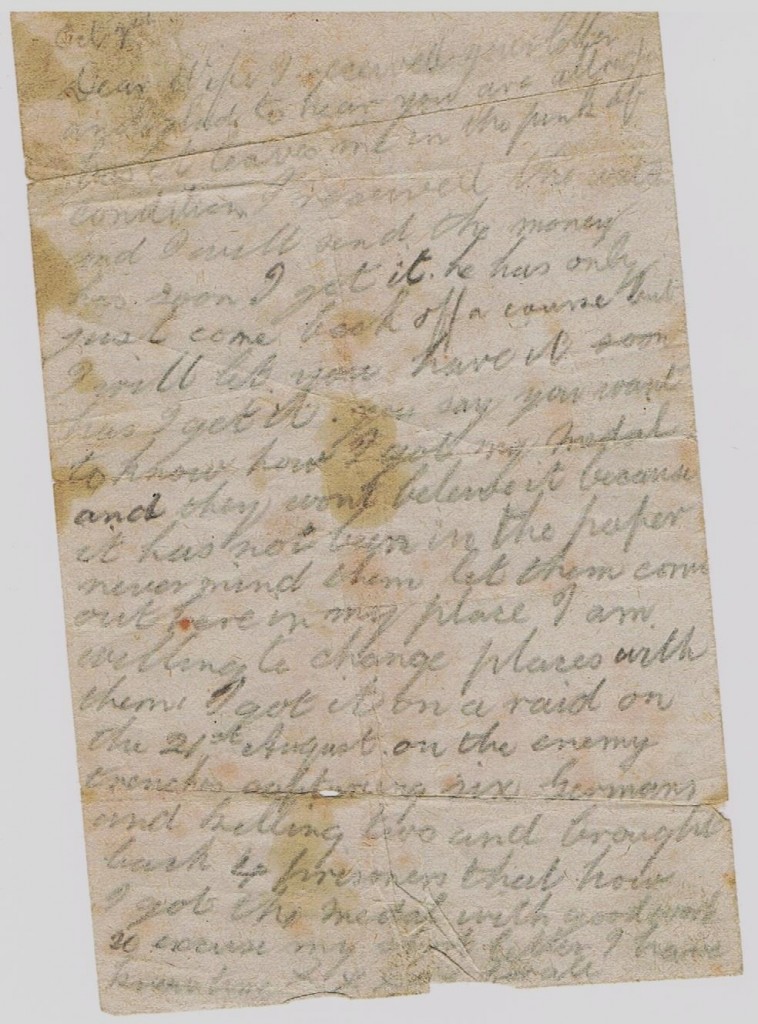

ABOVE: This is an original letter sent by Corporal William Shepherd to his wife Annie Amelia from the trenches in World War I. It tells how he won his military medal.

BELOW: This is a transcription of the above letter.

October 7th.

Dear Wife,

I received your letter and I’m glad to hear you are allright has it leaves me in the pink of condition. I received the watch and I will send the money has soon I get it. He has only just come back off a course but I will let you have it has soon has I get it. You say you want to know how I got my medal and they won’t believe it because it has not been in the paper, never mind them let them come out her in my place I am willing to change places with them. I got it on a raid on the 21st August on the enemy trenches capturing six Germans and killing two and brought back 4 prisoners that’s how I got the medal with good work so excuse my short letter

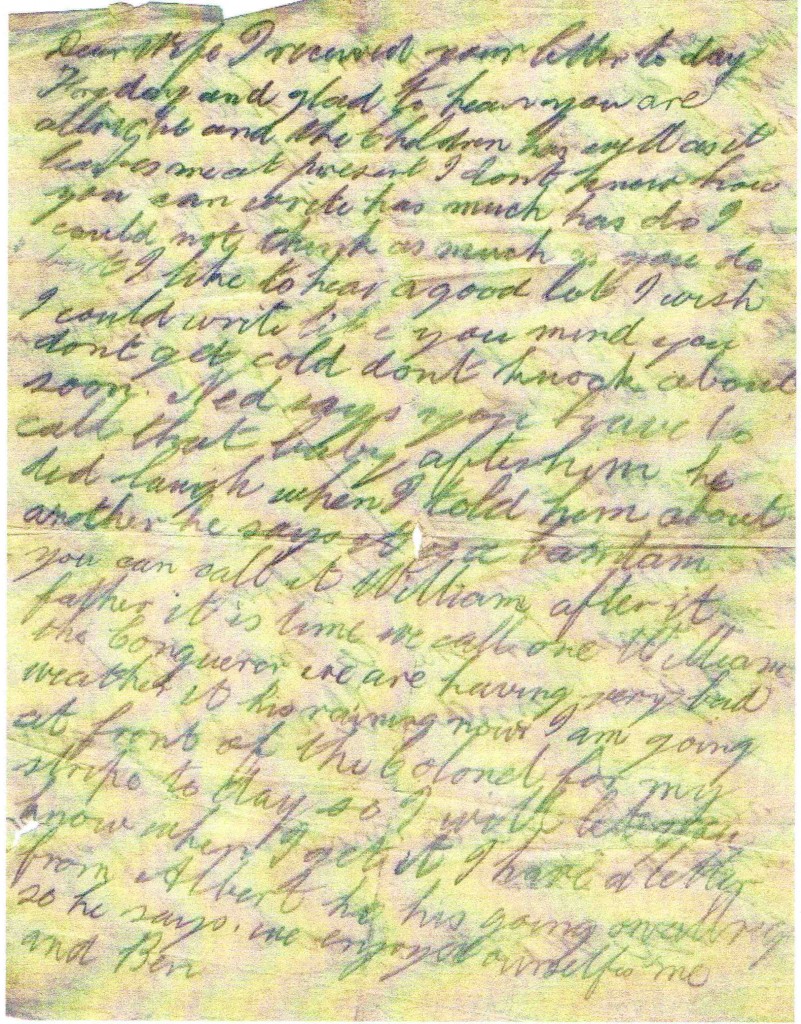

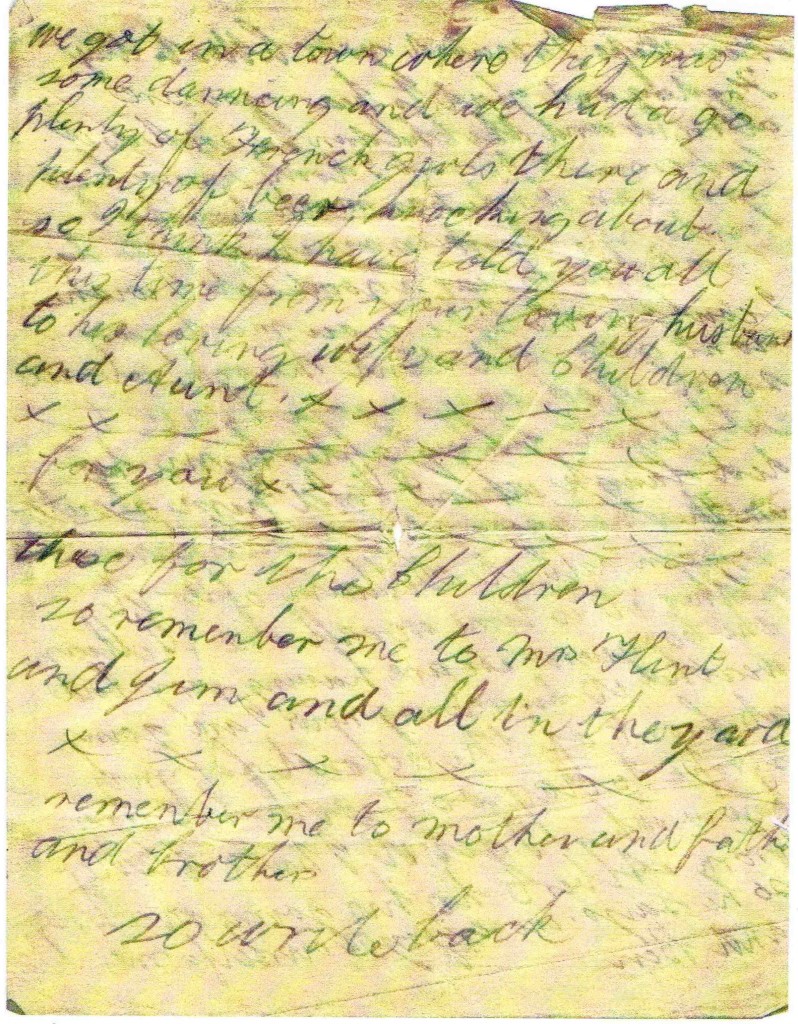

BELOW: Another letter from Corporal William Shepherd to his wife Annie Amelia during World War I.

BELOW: A transcript of the above letter.

Dear Wife

I received your letter today Thursday and glad to hear that you are allright, and the children as well as it leaves me at present. I don’t know how you can write has much as you do, I could not think as much as you do, but I like to hear a good lot, I wish I could write like you, mind you don’t get cold, don’t knock about too soon. Ned says you have to call that baby after him he did laugh when I told him about another, he says if it is boy you can call it William after its father, it is time we called one William the Conqueror.

We are having very bad weather it is raining now. I am going at front of the Colonel for my stripe today, so I will let you know when I get it. I have a letter from Albert he is going on allright so he says, we enjoyed ourselves me and Ben, we got in a town where there was some dancing and we had a go, plenty of French girls there, with plenty of beer knocking about.

So I think I have told you all this time from your loving husband to his loving wife and Children and Aunt xxxxxxxxxxxxxx for you xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx these for the Children.

So remember me to Mrs Flint and Jim and all in the yard. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Remember me to mother and father and brothers.

So write back.

_____________________________________________________________________

JOSEPH WALKER M.M.

Regiment: York and Lancaster

Rank: Sergeant

Service No: 313 745

Enlisted: 29 August 1914

Killed in Action: 17 September 1917 – Aged 23

Born in Killamarsh in 1894, the son of Robert and Elizabeth Walker, Joe lived at Highmoor and later at Norwood. The 1911 census shows that he was employed as a ‘Colliery pony driver underground’, probably at Norwood pit.

After the outbreak of war in 1914, Joe walked to Sheffield with his Killamarsh pals in order to ‘join up’.

He was enlisted into the York and Lancaster regiment on 29th August 1914. Joe was trained at Pontefract, Yorkshire with the 3rd (reserve battalion) York and Lancs.

Details of Joe Walker’s Service taken from army records:

13th July 1915

Posted to France with the 7th Battalion York and Lancs.

20th August 1915

Invalided home wounded, injury described as “bullet wound right arm severe”.

2nd January 1916

Returned to France posted to 8th Battalion York and Lancs.

23rd July 1916

Appointed Lance Corporal in the field.

2nd October 1916

Wounded and sent for treatment

10th October 1916

Rejoined the Battalion

20th October 1916

Appointed Corporal

3rd December 1916

Awarded Military Medal

19th April 1917

Appointed Lance Sergeant

3rd June 1917

Appointed Sergeant

17th September 1917

Killed in Action

Joe survived the battle of the Somme, only to lose his life a year later in 1917.

He is commemorated on the Tyne Cot memorial at Passchendaele, Belgium on panels 125 to 128 in the south rotunda of the memorial.

______________________________________________________________________

My Grandfather John Mangham appears on the Killamarsh war memorial and also on the Thurnscoe memorial he was killed 5/11/1918 and he is buried in the Artres communial cemetary in northern france with 5 of his mates he was the son of Samuel Mangham and married to Alice Morris at the time of his death his home addres was 8 King st Thurnscoe

Athol Frederic Swindle’s original battle field cross is now in St Giles Parish Church, it was taken there by myself after the old Congregational Church closed. It used to stand behind the font towards the back of the Choir stalls and each Remembrance Sunday members of the church would fix their poppies to the front of the cross.